28. Head empty

In which I talk about coping when life throws way too many curveballs

When I resumed this newsletter in June, I set a goal of posting at least every other week, which I have so far managed to do. But it’s now the middle of the last week of August and I’m still staring at a blank screen. I wish there were some eloquent way I could write down the number and depth of the sighs I’ve heaved since I sat down to write this an hour ago.

My current struggle stems from a number of things, foremost of which is the way the current state of the world has permeated my mind and the worry about where we’re headed has woven itself into the fabric of my daily life. As for the other things, well, let’s just say that it’s nice if you can occasionally block out the multilayered catastrophes exploding around the world and just be thankful for the stability of your own life—your job, your house, your happy, healthy self. Unfortunately, there’s no switching off for me right now—there’s no respite in work and in some aspects of my personal life.

In her praise of Madeleine Thien’s The Book of Records, the journalist and novelist Xinran wrote ‘. . . art and ideas are often born in the margins, in the spaces where survival is a daily act of courage.’ I have so much admiration for those who can still write and create art in the midst of pain and fear, and the way their courage can take the shape of a painting, a poem, a story.

My response to personal turmoil has often been unproductive—I just tend to go completely silent. Sometimes, it’s a deliberate choice. When something quite awful happened to me in my early 20s, I kept writing the events down in my journal and then tearing the written page off. I didn’t want to inflict my pain on the people I loved, so I got rid of all evidence of it, fully aware that I was protecting the guilty.

I think this is why I can articulate certain kinds of pain to other people, while being secretive about the rest. I am, for better or for worse, a proud person, and my pride extends to friends and family whose good names I am fiercely protective of. I just cannot divulge the specifics of the things that are weighing me down when good friends or members of my family are involved or if they will be affected in some way. I’m not sure if I was brought up this way or if, having grown up in poverty, I’ve always had this conviction that my reputation is my most prized possession. (And yes, I can hear John Proctor yelling ‘Because it is my name! Because I cannot have another in my life!’ in The Crucible while I’m writing this.)

So, anyway, with all this pent-up sorrow and worry, when withdrawing into my turbulent inner world doesn’t help, I am once again finding solace in the usual things—art and books.

My husband found a piece of card that I was using as a bookmark and said, ‘That’s a lovely picture. You should be selling those bookmarks!’ The picture he was referring to was a floral doodle that I made while playing with highlighters, which goes to show how sophisticated his taste in art is.

However, it did get me thinking that I should make some pictures that can be printed as bookmarks. The Philippines is the guest of honour at the Frankfurt Book Fair this year, so I’m creating a few little watercolour paintings featuring animals that are indigenous to the Philippines. Here’s the first one with a baby Philippine forest deer.

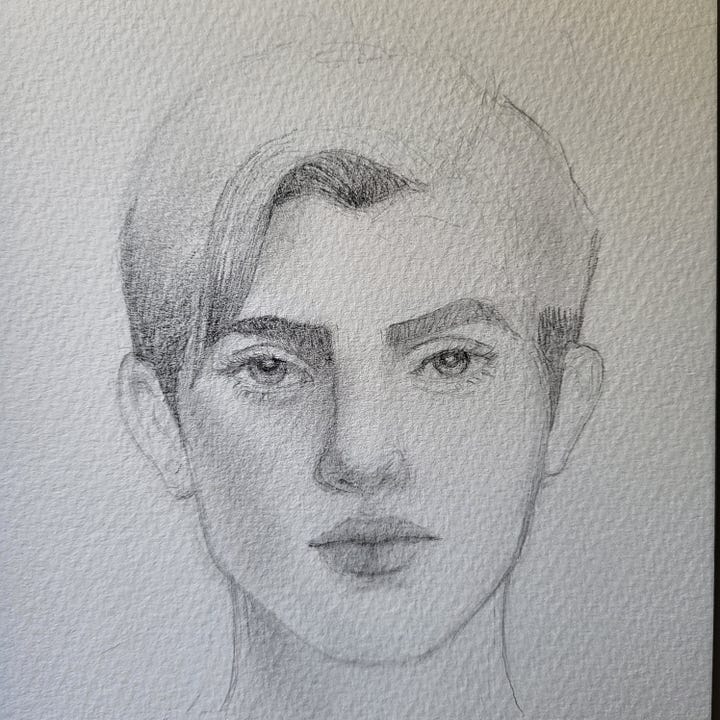

Also, I’ve been drawing men’s faces. Granted, their features are quite feminine (I blame my references), but I do believe I am starting to get the hang of this.

I am still very much into my E.M. Forster reading project. I’m now reading Where Angels Fear to Tread, the humour of which I am absolutely enjoying. There’s a part in chapter 2 that had me cackling. Philip Herriton, who rushed to Italy to stop his widowed sister-in-law Lilia from marrying a young Italian, is being his usual condescending self as he tries to convince her to break off her engagement to Gino. Moved by her declaration that she can’t break it off, he tells her, ‘...I have come to rescue you, and, book-worm though I may be, I am not frightened to stand up to a bully.’

It’s the succeeding paragraph that made me laugh: ‘What follows should be prefaced with a simile—the simile of a powder-mine, a thunderbolt, an earthquake—for it blew Philip up in the air and flattened him on the ground and swallowed him up in the depths.’

He gets a mouthful from Lilia, who has simply had enough of her in-laws’ controlling ways. And then, even more deliciously, Gino tells him that he and Lilia are already married, so there’s no engagement to break off.

I don’t know why I even try to question my love for Edward Morgan when his books are peppered with gems like this.

I’ve written about how the books I’m reading have been having conversations with each other. I’ve realised that I’ve been pairing my readings recently, tending to read together certain books that seem to speak to each other.

The first pair isn’t really surprising, as Christina Sharpe’s Ordinary Notes references Dionne Brand’s A Map to the Door of No Return, but reading them side by side has heightened my appreciation for both books.

I didn’t really know anything about John Berger until a couple of years ago, when I discovered on YouTube the seminal 1972 BBC series Ways of Seeing. I got the book based on the series, and I’ve been ploughing through Berger’s catalogue since. His beautiful meditations in Bento’s Sketchbook prompted me to start reading Spinoza’s Ethics, which, I must admit, was quite hard to get into initially as it reminded me so much of my struggles with geometry theorems in my high school days. Last week, I chanced upon Madeleine Thien’s The Book of Records, which features historical figures, including Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin and Spinoza. Having read Thien’s essay on Spinoza, I am now reading their books together—a literary and intellectual feast in which my troubled mind has found some respite.

What is it about books and art that provides much-needed comfort? For me, creating things and reading books are actions that take place in the liminal space between my outer self and my inner one—an area that’s untouched by the worries that plague those two halves. There is safety here, where desires—to make something, to visit other worlds and other lives, to find enlightenment and nourishment in someone else’s words—are met.

As Dionne Brand writes in A Map to the Door of No Return: ‘Writing is an act of desire, as is reading. Why does someone enclose a set of apprehensions within a book? Why does someone else open that book if not because of the act of wanting to be wanted, to be understood, to be seen, to be loved?’

In Ordinary Notes, Christina Sharpe declares: ‘Books … have always helped me locate myself, tethered me, helped me to make sense of the world and to act in it. I know that books have saved me. By which I mean that books always give me a place to land in difficult times. They show me Black worlds of making and possibility.’

Worlds of making, worlds of possibility—the visual arts allow us a peek into these as well. And to experience art, either through viewing or making, is to live through a moment of depth. In Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos, John Berger posits, ‘The deeper the experience of a moment, the greater the accumulation of experience. This is why the moment is lived as longer. The dissipation of the time-flow is checked. The lived durée is not a question of length but of depth or density.’

Maybe that’s what reading and making art give me—a way to endure the pain of living through moments that are dense with beauty and meaning.

Creating art and ingesting literature—this is how I’m surviving my own little earthquakes. There’s no courage in this, just a constant witnessing of days trickling past and marking them with words, with tiny bits of art, with my eyes wide open, with—as Berger puts it in his essay ‘I Would Softly Tell My Love’—hope between the teeth.