21. Some of us will not make it

In which I talk about our struggles in the face of impending madness

At the beginning of the pandemic, I started writing an essay that was prompted by a news report stating that 95 percent of hospitalised Covid patients in England had underlying health conditions. The essay was originally a reflection on my poor health as a child growing up in an impoverished neighbourhood in Makati, a wealthy business district in the Philippines, and how my body still bears the scars of intergenerational poverty.

I added another section to the essay a month later after reading an article explaining why it’s the BAME population in the UK who had the highest mortality rates from Covid, which of course had a lot to do with systemic racism. My essay was turning into an introspective take on race and poverty, its shape defined by the increasingly dismal headlines that highlighted the recklessness and ineptness of governments run by corrupt right-wing politicians like Boris Johnson, Donald Trump, Jair Bolsonaro, Shri Narendra Modi and Rodrigo Duterte.

My intention was to carry on writing the essay until the pandemic was over. However, on the day the headlines declared that the worldwide death toll had passed 1 million, my own mother died from the disease. I was too devastated to finish it. Occasionally, I still look at it, wondering if I can muster the grace and courage to resume writing it and face down the emotional turmoil that would likely be triggered by it.

I mention these things because the day after the US elections, my social media feeds were filled with well-intentioned words of consolation and encouragement from people in and outside the US—words along the lines of ‘We will carry on fighting. We survived before, we will survive this time too.’

I understand the sentiment, but it’s hard to read those words and ignore the irony of seeing them in posts sandwiched between photos of dead Palestinians and bombed-out neighbourhoods in Lebanon. It’s hard to relish the joy of being alive without feeling guilty over those who are being displaced, starved, denied medical treatment, and bombed by a genocidal state propped up by Western governments. And how about those whose ongoing suffering has been completely ignored by the public because their stories don’t even make the headlines anymore?

This takes me back to the time of the pandemic, when the worst wave was over—vaccines were finally being rolled out and the medical community had refined their assessment and treatment methodology. There was a lot of relief as people could finally see the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel—survivors emerging from our collective deathscape, congratulating each other. All I could think of at the time was the fact of my mother’s absence from the mass of survivors, and how she, like the other people who had succumbed to the virus, was a victim of birth and circumstance.

I can’t help but think now of what it must be like to be born a Palestinian and be a refugee in your own land, to be a woman in Iran or Afghanistan, to be an Uyghur in China, to be a child in Yemen or Sudan, to be poor in the Philippines, to be undocumented in the US, to be a Jew in places that continue to other Jews, to be a Muslim where Islamophobia is the norm, to be the colour, gender or sexual orientation that’s targeted by fascist movements multiplying around the world. When a person’s survival is hinged on where they live and which demographic they belong to, what chances do many of us have in a world being rendered even more dangerous by these movements and the totalitarian governments that they’re propping up?

We can talk about being the light in the dark times ahead but we have to acknowledge that the light has already gone out and is right now being put out in many parts of the world. We can talk about surviving the next few years let’s be clear though that this assault by autocrats and broligarchs on human rights and global stability is a long-term one), but we can’t sugarcoat the fact that many people, despite their best efforts and everyone else’s good intentions, will not make it.

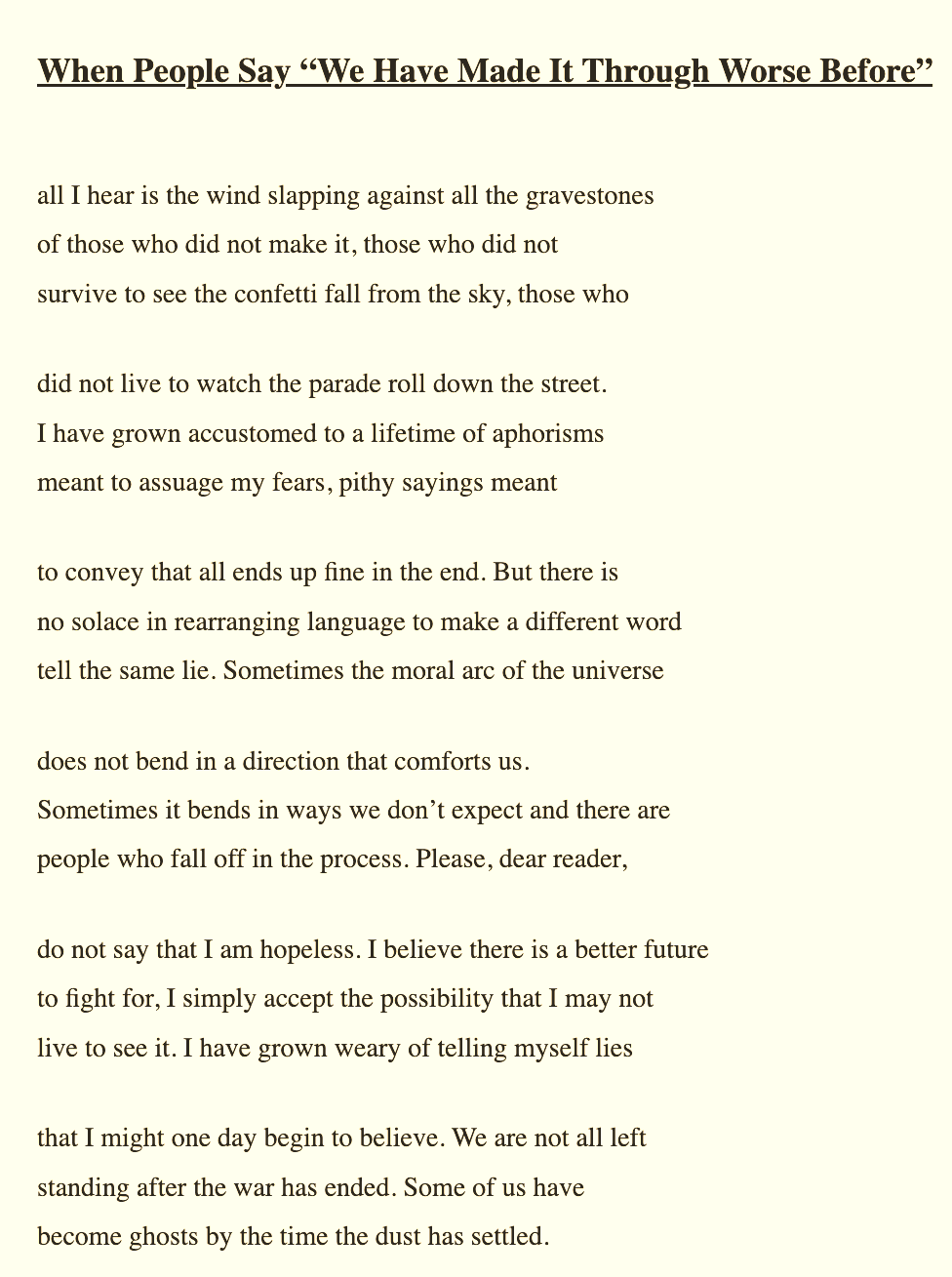

Clint Smith puts it beautifully in this powerful poem from his most recent collection, Above Ground:

This is not me saying there’s no point in trying to stave off the unprecedented levels of insanity that are about to be unleashed on the world, though. Hope and defiance will still be our response. We will never bend to power.

As Rebecca Solnit wrote the day after the elections:

They want you to feel powerless and surrender and let them trample everything and you are not going to let them. You are not giving up, and neither am I. The fact that we cannot save everything does not mean we cannot save anything and everything we can save is worth saving.

Some of us will not survive this, but it doesn’t mean we shouldn’t work as if all of us could. Doing this entails viewing our struggle as universal—that my right to exist is the same as a Palestinian’s right to exist, that the sovereignty of my country is on the same level as that of Ukraine, that a child in Congo deserves as much care as a child in the UK, that a life lost in Syria is as much a cause for grieving as one lost in the US.

Only when we recognise the intricate connections between our struggles can we have a fighting chance against the darkness that’s descending on us.

Reading in the dark

What are you reading these days? Here are the books currently on rotation on my bedside table:

Clint Smith’s Above Ground is a wonderfully moving, probing poetry collection that’s definitely worth digesting.

Rebecca Solnit’s Hope in the Dark, which became everyone’s favourite book when Trump was elected president the first time, is worth a revisit.

Recognising the Stranger by Isabella Hammad and The Question of Palestine by Edward Said are terrific side-by-side reads; you can also add Minor Detail by Adania Shibli.

Somber reading can be balanced by something entertaining. I’m rereading my favourite Discworld novels. First in the pile is Going Postal, and I have completely forgotten how insane this is (in a great, funny way, of course).

I’m also reading Vajra Chandrasekera’s The Saint of Bright Doors. This dark, multi-layered but very readable fantasy is a breath of fresh from the usual Western fare. The world in which the novel’s characters move is reflective of Sri Lankan culture and history, which makes for an illuminatingly fresh reading experience.